This text was commissioned by Filmform as part of a larger digitization project in which over 500 tape-based works have been digitally transferred and restored. In particular, it covers the so-called “DV era,” from the 1990s until the digital shift around 2010. Out of this rich material, three artists have come into focus for this text: Axel Petersén, Annika Ström and Annika Eriksson. The text moves in the field of tension between the artist filming, the people being filmed and the technology, and draws on the artists’ own comments and reflections on their works and processes to address shifts between dominance and submission.

DV (Digital Video) hit the market in 1995. As the first consumer-friendly digital tape format, it soon revolutionized both film, art and the amateur scene. Video tapes had a 60-minute recording time, better image quality than previous analog video formats, and the editing process could be handled independently, without needing to involve outside parties. All this enabled a working process where the hand could precede the mind, where art and technology could mutually influence each other. This led to a flourishing of video art and a distinctive language of the time, in which reality manifested itself more or less actively.

When Nisse invites Axel and his friend to a three-course dinner—Champagne mousse, duck breast with fruit sauce and rice, coffee and cake—he also wants to take the opportunity to shoot a porn movie in the shower. The camera is already there, you just need some initial instructions. After that, you can see where the mood takes you, if one thing leads to another, and how it turns out. The merits of the DV camera enabled an intimate connection with the surrounding reality, it could be there at hand while waiting for something to happen, or in order to make something happen

Axel Petersén, Söndagmiddag, 2005

Axel Petersén:

I have thought quite a lot about why I started filming, it was a bit unclear what I was doing with that camera. It was around the turn of the millennium just after high school and I found myself in many strange contexts. We were hanging out with older, wealthy gays, and there was a tension between us—young, old, rich, naive, we were engaged in some kind of cock teasing, you could say—and I think that on an almost unconscious level I tried to recreate that dynamic in my films, but with the camera as protection—I reversed the roles through it, it meant I could control and direct the situation.

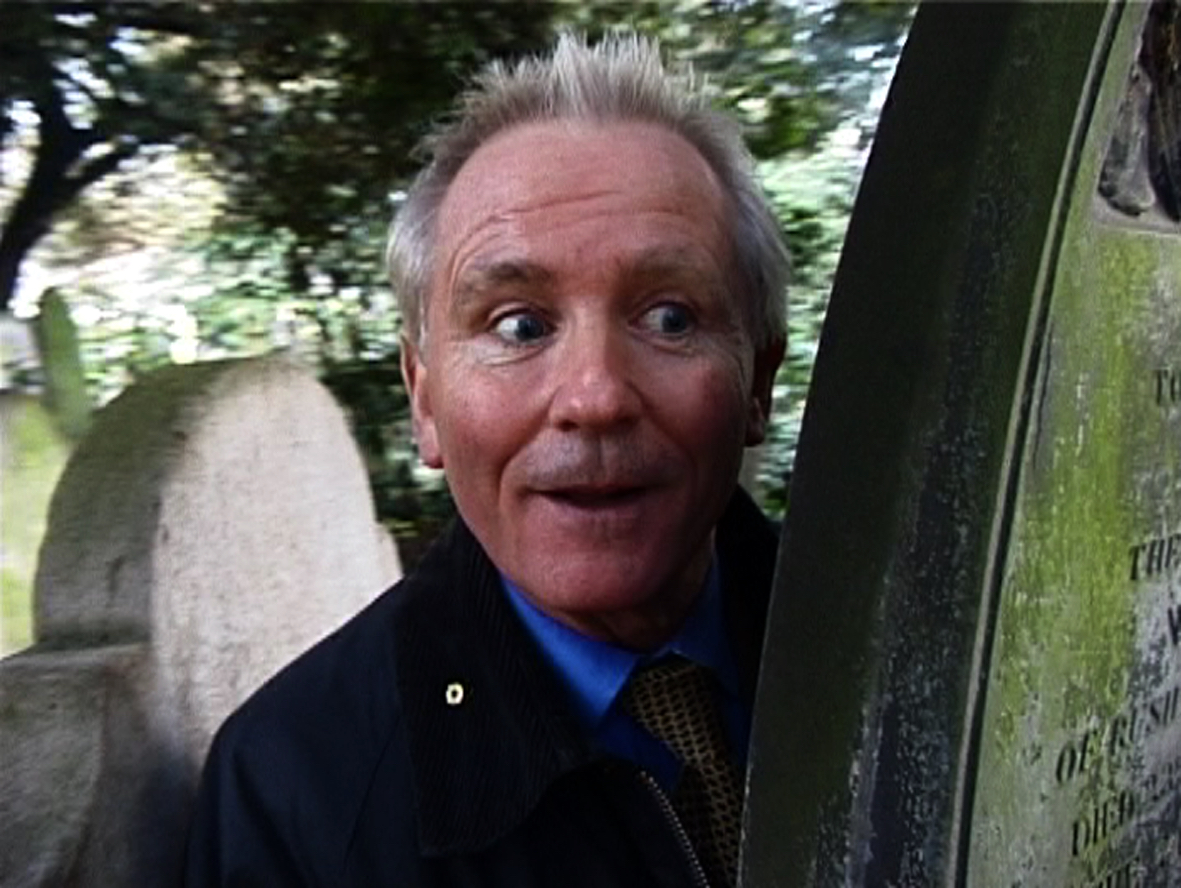

Initially, I filmed a lot and intuitively, but the same situations kept coming up. I mostly had a plan, but at the same time I tried to keep all doors open. When we met Nisse in Söndagmiddag (2005), the idea was that he would tell us about a kidnapping drama he had experienced with a drug addict roommate, but his suggestion when us two young guys came to his house was something else. The movie Brompton (2003) started with the protagonist (Allen Warren) contacting me because he wanted to shoot me. Tony in Close to God/Far from Home (2009) hooked me up on the street and then we were off, I started shooting in his barbershop. I have never made these films for shock value, but I was probably more ruthless when I was younger. The criticism I received at the beginning, when I began filmmaking, was about moral and ethical perspectives. Eventually, it made me involve myself more so that I became a more significant side character in the films. In the later short films, I am more ruthless with myself, I become a clearer subject.

I liked that it was direct and that I could act intuitively. I was driven by curiosity, I wanted there to be a nerve. In retrospect, I have realized that the first-hand perspective I used in the films was inspired by homemade porn.

Axel Petersén, Brompton, 2003

There is something about the size of the DV camera that is central to the situations that Petersén’s work provokes; the people in the frame are attracted to a situation and its possibilities, with the camera and a young man behind it. It is a performative situation that both depicts and brings reality to life. The size of the camera is, arguably, significant in this liminal space, where it is not perceived as unwieldy and intrusive, yet it is large enough to mark the event of facing a camera and being seen by it. Its presence evokes a certain mood and expectation, it is not a neutral thing but a catalyst associated with a sexual promise, driving the drama forward, albeit inconclusively. In art historian Ina Blom’s Autobiography of Video (2016), she argues for the camera as a subject in its own right, and that what is produced by the video camera is not a static representation but a living and thus constantly changing record of the world, dependent on the technical apparatus. She asks whether it is possible to imagine a narrative other than that of agency and if the power to perform is something that automatically belongs to the artist or the artwork, and what the consequences would be of a study that read video works from the idea that video could possess subject-like qualities and conditions for action. Of the affective properties of the video camera, she writes:

If numerous artists have used the lifelike durations of video to portray the self in process, video may also have used the desires invested in human self-portrayals for its own purposes. It may, for instance, have associated with their affective charge, their basic quest for contact and connection.

Ina Blom speaks of an “attest to an erotics of connection” and adds that the emotional dimensions of video can also be described through physical phenomena such as vibrations and contractions, as well as electromagnetic flows. Following a pornographic logic, the machine and the agents of sexuality, beyond concepts of good and evil, beyond love and reason, potentially conform to each other by probing and transgressing boundaries.

In light of the rise of the DV camera and the flowering of video art at the turn of the millennium, we can perhaps speak of a contemporary realism whose direction was closely linked to the camera in its capacity as active subject, along with both its possibilities and limitations. In other words, an interplay between art and technology which, together, evokes notions of truth from characters, mundane details, and the environment. In the filterless depiction, a contemporary ideal emerged, perhaps most clearly manifested in the breakthrough of the Danish film movement Dogma (Dogme95) and their joint manifesto from 1995, in which they pledged to use only hand-held cameras in their productions, never to alienate time or geography (i.e. the film would be set here and now), and to dispense with props, filters and lighting, with all personal taste and desire to create a ”work,” for the moment to supersede the totality.

Axel Petersen, Close to God/Far from Home, 2009

Annika Ström:

I always had my camera with me, like people have their cell phones now. I filmed aspects of everyday life that I found interesting, it could be a car being washed at a gas station, a woman getting on a bus in Indonesia—anything. I first looked at the material while editing and then composed it into collage-like videos that brought together different times, scenes and continents. Like a painting but with moving images and my own music as a soundtrack. The DV camera was a revolution with its 60-90 minute recording time. You could afford to be wasteful.

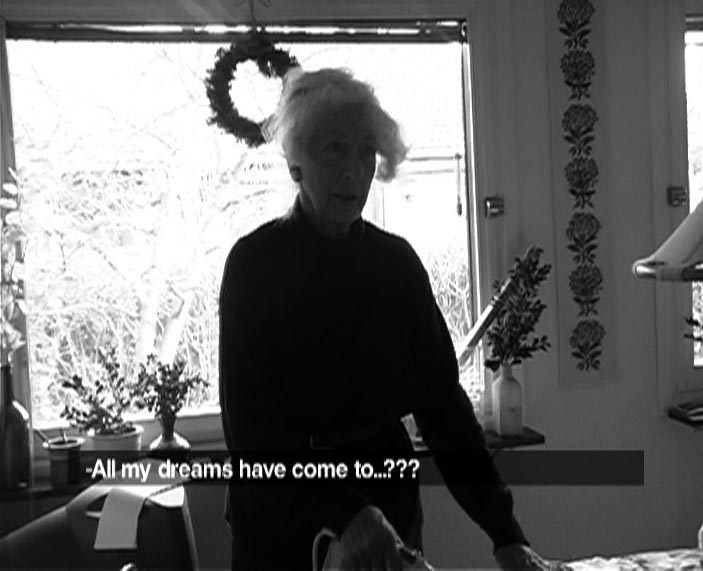

I filmed my family a lot. Since I moved abroad early on, I stayed at my parents’ house when I came to visit. They lived in a residential neighborhood in Helsingborg. The camera became a shield to handle the situation when I was there in the house, with all the preserved props from my childhood. A typical video is All My Dreams Have Come True (2004), my mother is ironing in the living room and I ask her “All my dreams have come true, what is it called in English?

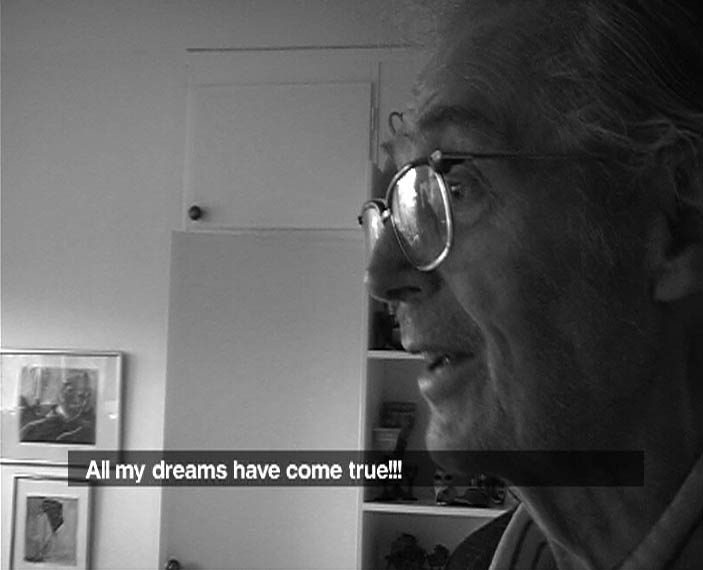

Then she turns to my uncle who comes out of his room and engages in the discussion (he knew fifteen languages). It’s a moment typical of what I was doing, evoking situations that became scenes in my films. Regarding that material, I was initially hesitant on whether or not to use it. My uncle was so ill and came into the frame so unprepared—he was the kind of person who always paid attention to his appearance—so at first I didn’t want to show him like that. In the end, it was actually Annika von Hausswolff who convinced me to use the scene, “he’s the hero” she said, “he’s the one who knows”.

Annika Ström, All My Dreams Have Come True, 2004

In retrospect, several works from the DV era have a seismographic effect, there is an incipient ease and a very direct relationship to the possibilities of technology and intimate interactions – in the dawn of the era of reality TV, before social media and the panoptic ubiquity of surveillance cameras. When Annika Ström describes her relationship with the DV camera as “a basket to collect clips in,” she also mentions that she never used her mobile phone for the same purpose despite its video function “because today we live in an overproduction of everyday impressions and there is nothing to add there”—this something, this possibility that DV offered, it has disappeared. In his lecture ‘No time,’ political philosopher and critic Mark Fisher argues that the marriage of art and technology reaches its turning point precisely in this period, in the mid-1990s. In the context of the moment he describes, 2013, the innovations of technology thereafter primarily become a system focused on consumption and distribution, so its functions tend to drag culture down (in a nostalgic direction) rather than drive it forward. There is no time to focus because of the expectation to constantly be available and respond to “parasitic communication,” media technology means constant interruptions that compromise the quality of attention we are able to give to the world. The capitalist realism articulated by Fisher is based on the dictum of philosophers Slavoj Žižek and Fredric Jameson, that “it is easier to imagine the end of the world than the end of capitalism”— a statement informing our actions and imaginations in every conceivable field: language, intimacy, and fantasy.

In The Revolution of the Ordinary (2017), literary historian Toril Moi articulates a perspective based on the same problem: if a society loses its faith in language, it also loses its grip on reality. Through the philosophy of everyday language—which perceives language as statements, i.e. actions in the world—Moi reintroduces what she perceives as a radical, critical potential that has remained latent in an outdated theoretical framework. It consists of a belief in the power of example, an insistence on a theory that dares to present itself through details, and a trust in the world and in the relations of language. “In modern society, a person risks living his or her whole life in unreality if he or she does not learn to see … If we do not direct our attention towards the world around us, we will either remain empty, or completely predictable”, writes Moi.

Annika Ström, All My Dreams Have Come True, 2004

Annika Eriksson:

I’ve always considered myself to be portraying an over-reality—reality amplified into something greater. When I first shot Two Men and a Sheep (1995), I had just moved to Stockholm. I had little money but a lot of time so when a pet fair was organized in Kungsträdgården, I went along. There, I witnessed a scene: two men sat with a sheep in a pen, cuddling it. I felt intuitively that I had to stage that. It’s very important for me to find the right people to work with, who are open to what I want to do. I am always very clear in my instructions so that they are prepared for the scenario that will be unfolding, and often, as in the case of this video, everything happens in one take.

I funded Two Men and a Sheep by sending out a letter to men in the art world asking them to support a project about men and tenderness. By contributing SEK 100, they would receive a signed photograph of the event, I promised them anonymity and that they would later know where the project would take place. 72 men sent money, which funded the work. An open invitation was sent out to a venue in Östermalm, where I had set up a surveillance camera in the ceiling. The event went on for four hours. The two men in the pen were instructed to keep petting the sheep and not leave the area. I was not present in the room but could follow what was happening via a monitor in a side room. I wanted the visitors to be confronted with their own reaction, not to meet me, the one who had the potential to explain what was going on. I liked the ambivalence and the fact that the audience became part of the work. There is also something kinky about the whole situation. In retrospect, I have realized how many different levels there are in this work, but I did it without thinking too much, it was hand before thought!

Annika Eriksson, Två män och ett får, 1995

The work was later performed in Berlin and London. According to the artist, the repetition of its structure should not be seen as a repetition of an event but as an exploration over time, where the scene will be played out differently each time, depending on the different actors, the audience and the location. The work’s premise relies on a degree of unpredictability. The German version, for example, involved one of the two men having an outburst: he started shouting at the surveillance camera (the artist) that he felt trapped and exploited. Actually, the power relationship suddenly became very physically tangible, the premise of the work became provocative. Everything that happened was captured on tape and became part of the work.

“The ‘human scale’ or humanistic standard proper to ordinary life and conduct seems misplaced when applied to art. It oversimplifies,” writes Susan Sontag in her essay ”The Pornographic Imagination” (1967). Sontag argues that the role of the artist is to transgress the boundaries of the conventional socially functional mode of interaction regulated by moral obligation. To instead venture out into the outer limits of consciousness and then, through the art they produce, report back on what they have experienced out there.

In this report, focussed upon the turn of the millennium, I have looked at the art produced by three artists and the situations they evoked with the support of the camera. What I have found is that these three artists — Axel Petersén, Annika Ström and Annika Eriksson — all share a curiosity regarding the social potential and dominance of video, but also its capacity to act as a shield in a charged situation. The presence of the video camera creates an uncertain moral situation whose unpredictable outcome also sharpens the presence of the viewer.