Amin Zouiten: Why film?

Madubuko Diakité: My basic understanding of the power of films was acquired in Nigeria, where I spent my teenage years. After divorcing my father, my mother married a Nigerian journalist and sent us four kids to live with him in Nigeria. Going to the movies was my biggest past-time, even though the theaters were outdoors and we were constantly stung by mosquitoes. I returned to New York at 16, did two years of hard time in the US Army, and was on my own in New York after that. In the spring of 1968, I’m living in an East Village apartment in New York when I saw a program by Bill Cosby, an actor and a comedian on TV. He was starring in a film about how black Americans were treated in American movies at the time. It was a shocking film for me because I had never thought of how demeaning to black people those images were. He described how humiliating they were being portrayed: as mammies, clowns, coons, and servants. Always in some kind of subhuman character. It was then that I said to myself: “I want to change that. I want to contribute to something different. I think I’ll learn how to make films.” I had a camera, and I was an amateur photographer. At around the same time, I met a Danish guy who said to me “Oh, you can learn how to make films in Denmark” I said, “Really? What’s the name of the school?” He didn’t know, so I went to the Danish counselor, which was located on Park Avenue in New York City, and they gave me the address. I wrote a letter to the school, and they wrote me back in English saying, “Yes, you’re very welcome to come here and study filmmaking.” New York City in 1968 was very rough and the 1960s in the United States was violent and I suggested to my fiancé at the time, Elaine Bosak, that we should leave America, period. She agreed with me, so, we packed our bags, sold our apartment, and flew to France, Paris.

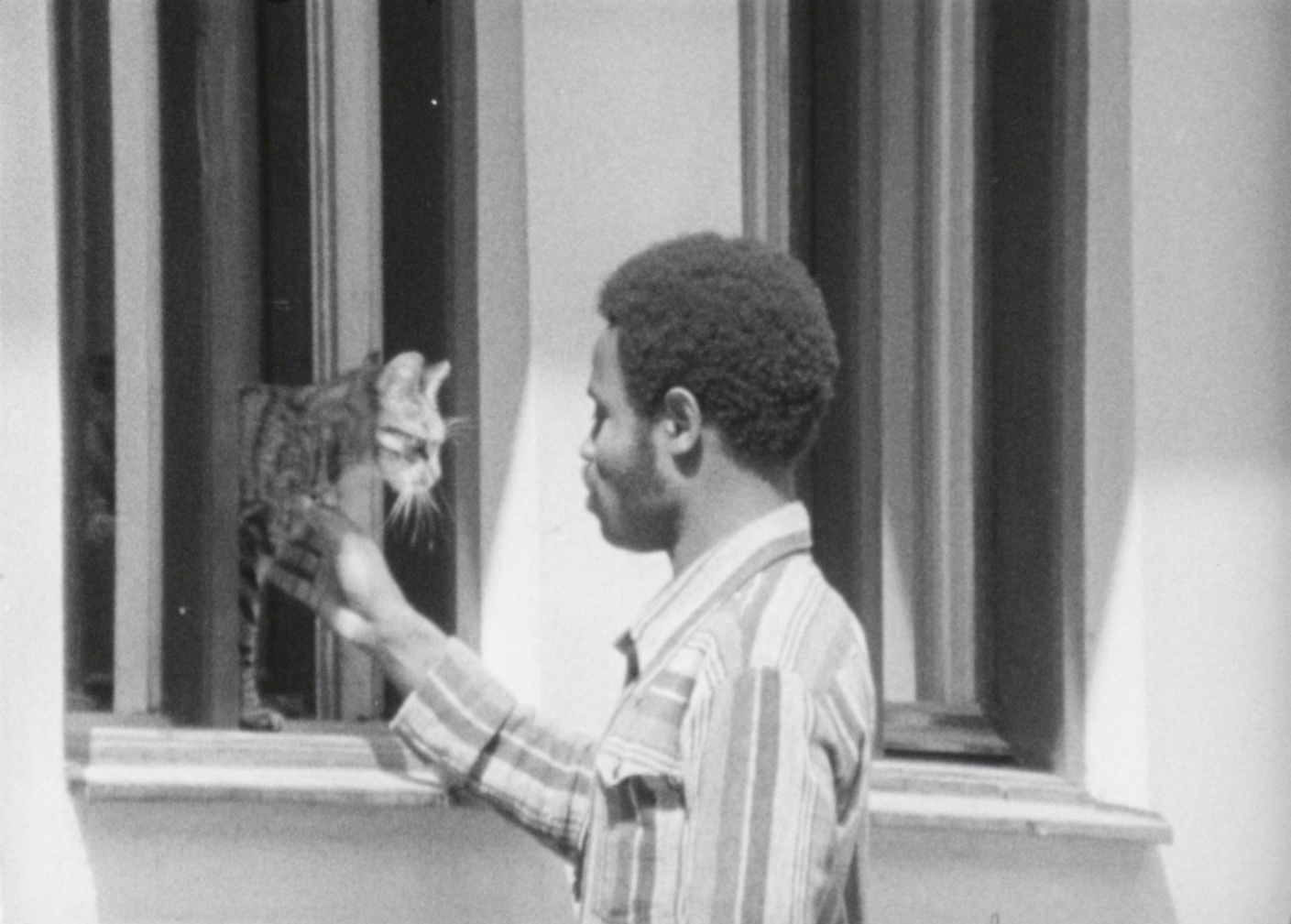

Dreams of G, Madubuko Diakité, 1970

AZ: You arrived to Paris in May 1968?

MD: Yes, we went to Paris at the end of May. A week later, an American with whom we flew over on the same plane suggested we come up to his apartment for coffee. His place overlooked Boulevard Saint-Germain. By the time we got up to his apartment the police (the Gendarmes) were rioting on the street and were taking everybody, students, tourists, and whomever they could grab, and were just pushing them into wagons. If you couldn’t run, they would take you away. The French ‘Gendarmerie’ were very bad, we were shocked. We saw all this from his balcony, so I said to Elaine, “Let’s get out of here, we don’t anything to do with this”. We bought a Citroen 2CV for $100 and drove through France, through Bordeaux to Biarritz, where we spend the night in a hostel overlooking the Atlantic Ocean. The next day we drove to Spain, through Bilbao, Vitoria, Burgos on to Madrid, where we saw another student demonstration. We drove down to Toledo and then we went down to Alicante. While there, we realized that it was no point trying to get a hotel room because of the tourists, so we bought a tent and lived in camping sites along that coast all summer.

AZ: Was there time to think about cinema within all of this?

MD: Yes, there was time to think about what I was going to do. So, I said, “I got the acceptance letter, I’d better go to Denmark”. I got to Copenhagen and went to the film school. I said, “Here’s a letter, when does the courses start?” They said, “You have to study Danish for 18 months, and then you can come back.” I said, “No, this is wrong. I’m not going to do that”. They said, “If you don’t want to do that, we are sorry.” I left feeling very disappointed in Denmark. So, I went to a café where I met a guy from Jamaica. I told him my story, why I was there and what happened. He said, “If you don’t like this place, you can go to Sweden. You could probably study film in Sweden”. He showed me how to get to Sweden on a map and I got into my newly bought Volkswagen Beetle. I was the first one off the boat but the last one to leave the harbor. The customs guy came and started looking through my suitcase and opening it up. I said, “Why are you doing this?” He said, “Because people who look like you, they sometimes bring drugs into this country.” “I’m not bringing any drugs into the country”, I replied slightly angry. “That’s not my purpose here.” He closed the suitcase. Anyway, when I came [to Malmö], I had a little transistor radio. I went to buy batteries for my radio and I saw this African guy standing, looking through records and I said, “Hey, you’re the first African I’ve seen here, are there many Africans here?” He said, “Yes, we’re quite a few living in Lund”. He said, “Come to Lund.” and he gave me his address. I got to Lund and all of a sudden Sweden looked interesting. It was a sunny day in September and if you ever want to see something beautiful, you go to Lund on a sunny day in September. I found the guy, this African guy and he said, “Oh, I’ll take you over to ‘Internationella’, where you can rent a room”. I met a couple of other guys there, one from South Africa and they all said, “Stay here, school is free here”. One of them took me to the university office and I was able to register to study Sociology on that same day. In those days, you didn’t have the situation you have today, with ninety thousand kronor per year for foreign students. No, you just walk up and say, “I’m want to study here in Sweden”. That’s thanks to Olof Palme. He made it easy for foreign students to come here and study. He was very sympathetic towards the poor.

Dreams of G, Madubuko Diakité, 1970

AZ: You didn’t start studying film?

MD: No, not then. The guy from South Africa, (who was a medical student), and I hung out lot, and when I told him that I wanted to learn how to make films, he said, “I know a guy who lives here, making films”. He took me to room 100 in the same student housing as I was living at. He knocked on the door and here was this very tiny polite man whose name was Navid, but friends called him Tony. When I told him “I want to make films”, his reply was “I guess you came to the right place. Meet me tomorrow and I’ll introduce you to a film camera in case you’ve never seen one”. All this took place in 1968. The next day I went to the address he gave me, and we went outside because he was making a film. He handed me a Beaulieu camera and became the first person to introduce me to film and film cameras.

AZ: This was the first time that you used the film camera?

MD: Yes, first time. He showed me how to Aim, Point and Shoot. I shot a few seconds of a film that he was making called Green leaves of Winter, at the time. Then in 1969, I decided to go back home to join my fiancé, Elaine, but still with filmmaking on my mind. I found a school in New York, called The New York Institute of Photography. They had courses in documentary filmmaking and the teacher was a man named George Wallach, who was an old Hollywood cameraman. He taught me how to make films. We learned how to make films with the cameras we used there. We had Bolexes, Kodak, Bell and Howells. We also had a Beaulieu, one Arriflex BL, and an old Mitchel. He also taught us how to use Nagra tape recorders and how to light scenes for filmmaking while I was there. We also saw hundreds of films by German, Russian, Italian and American filmmakers. And we learned how to write scripts for documentary films.

AZ: How did your perception on filmmaking change during your studies?

MD: Before I went to Paris, it was only junk films playing on theaters in America. My girlfriend at the time said, “Do we have to go see another John Wayne movie?” I said, “No, we don’t. I hate him anyway.” Clint Eastwood, I hate him, too. These guys were all about ‘bang, bang’, killing and shooting people. When I came back from Europe and finished the six-month course in film, my taste matured and I began to discover the beauty of French films that were shown in New York. Jean-Luc Godard and all the other filmmakers, the so-called underground filmmakers such as St. Clair Bourne, The Maysles Brothers, Andy Warhol and so many others. I saw films by people who were making films for love, not for money but because they love the art of film. I think my trip to Paris helped me to appreciate that, because in Paris, I saw only one commercial film. In the film school in New York, I was seeing all kinds of documentary films and art films. By the time I finished, I was a whole new person. I made a little eight-minute film about Biafran children who were suffering in Biafra, eastern Nigeria. When my friend Navid visited us in New York he told me, “They opened a new film school in Stockholm. It’s called the ‘Swedish Film Institute’. Why don’t you come and see if you can get into that film school?” So, I came back in July of 1970. During that time, I bought some cameras. I bought myself a Bolex and a Kodak and brought three 16 mm films I had made in New York.

En dag på Mårtenstorget i Lund, Madubuko Diakité, 1981

AZ: You came back to Lund to make films?

MD: I came back, loaded and there was one film that I made that was only half completed. It was For Personal Reasons, a film I made in New York but hadn’t put the sound on. I began to write to film producers here in Malmö. I wrote to all 37 film producers who were in the phone book and only one replied. It was a man working for Swedish Television in Malmö. He said, “Come in. I’d like to see the film”. I went in and I said, “I made this film in New York – it’s about a young man who gets angry but he’s influenced by Malcolm X, by all the events around him and he decides to shoot somebody, a police man”. So, they kept it. After one week, no call. Two weeks. Three weeks. I picked up the phone and said, “Did you see my film?” “Yes, we saw it. We’d like to buy your film.” This was 1970. It was still without sound. I had a soundtrack, but the two weren’t married. They took me upstairs to a room with a Steenbeck editing table and I said, “Oh, my God, a Steenbeck!”, you know Americans – “Oh my god! to everything”. [Laughs.] He said, “You can edit your film here and let us know when it’s done”. I edited it, they made a copy and they kept it. That was in 1971.

AZ: At this point you had already been working on other people’s films?

MD: In 1969, in New York I started working with other people making films. One guy was very helpful, he was a filmmaker for a long time. He made commercial films for other people. We even ended up editing a film for Monsanto Chemical Company, people who made Agent Orange. The film we made was not about Agent Orange, but it was about fertilizer. Terrible stuff. The boss was a really ugly, racist man. He couldn’t pronounce my name, so, he said, “Can I call you, Sam?”. The guy who got me the job, his name was Boris [Bodé]. Boris knew everything about filmmaking. He knew about camera-work, he knew about sound and he knew about lighting.

AZ: You were a cinema worker basically?

MD: Yes, but it was good work because I learned a lot. I learned how lighting should be positioned and I learned about sound. I would use the Nagra tape recorder, which was a big help because when I saw that William Greaves was making a film – he put a notice in [the magazine] Backstage saying that he needed a sound technician. So, I answered, “I’ll do the sound for you”. He said, “You know how to work a Nagra?”. I said, “Yes, I do”. The job went well. He said, “Thank you very much. Here’s your money goodbye”. That was the last I heard from him.

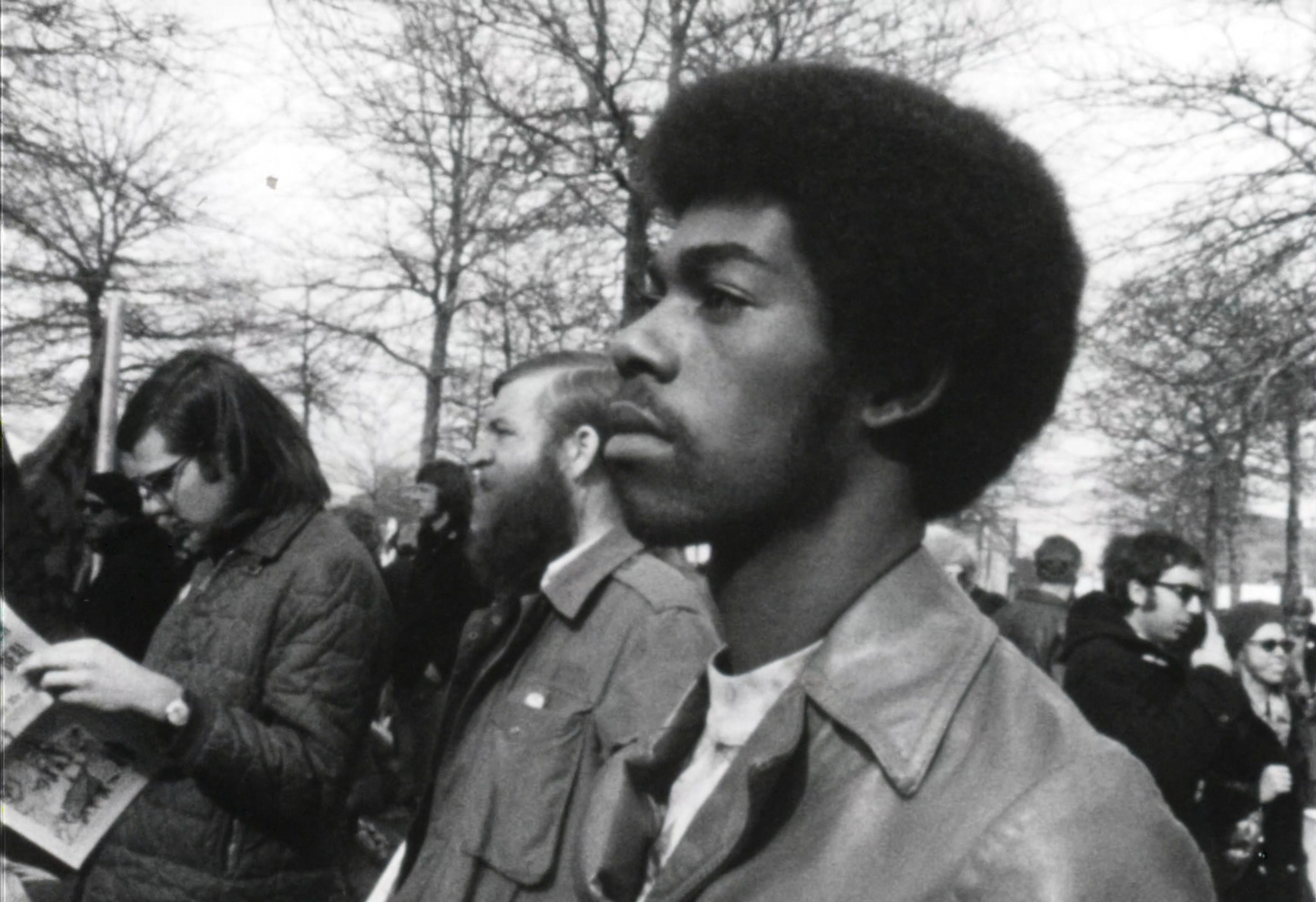

For Personal Reasons, Madubuko Diakité, 1972

AZ: Then when you came back to Sweden in 1970, you concentrated on your own films?

MD: Yes, when I came back to Sweden it was all my own stuff. First For Personal Reasons. I sent it to the Grenoble Festival of short films, and I was awarded a Special Mention. So, when I came back to Sweden, I went to SVT. “Did you show the film yet?”. They said, “No, we haven’t shown it yet”. I had the paperwork to show that it won the Special Mention. “Oh! Well, then we’ll look for it, we’ll try and find it and put it on TV in one of our programs”. But they had lost the copy that they made so they paid me again for a new one. Then it screened on TV and of course, there was some reaction. One guy writing in ‘Kvällsposten’ said, “Oh, police murders in America, bla, bla”. [Laughs.] Well, I answered him. This was a question of self-respect and dignity and that black people were getting shot all the time there. Nobody ever writes about them or makes films about them. That’s why I made it and that was my subject.

AZ: What was the reception of For Personal Reasons between your closest colleagues and closest friends, who were also making films?

MD: They were very proud of it. But unfortunately, strangely enough Navid and I became rivals. All of a sudden here’s the guy who taught me how to hold a camera. I go away to New York. He comes over and encourages me to come back. When I come back with all these films, two cameras, editing equipment he suddenly found himself a rival. But other people did appreciate my work.

AZ: Were there other public reactions than let’s say the one in ‘Kvällsposten’?

MD: No, there was never another reaction, like ‘Kvällsposten’. That was the only nasty reaction. Then I made my next project in Lund, Det osynliga folket. I had gotten admitted to ‘Filmvetenskapen’ [cinema studies] at the film institute in Stockholm. The professor was very kind. Loving towards me. He was a wonderful man, Rune Waldencrantz. All the books were in English. [Laughs.] That was great.

AZ: That’s a big difference from the Danish film school.

MD: Huge difference! Different filmmakers came. Bertolucci came. Then Wiseman came, Frederick Wiseman. Another person I met with was Vilgot Sjöman. Whom I loved. I told him I loved I am curious, Yellow. I said, “Do you make much money from it in America?”. He said, “No, they [Janus Films] gave me $5,000 for the movie”. Then they went off and made millions on it because they didn’t talk about the ideology behind the film, they showed it as a sex film, which is how I saw it in New York.

For Personal Reasons, Madubuko Diakité, 1972

AZ: But For Personal Reasons and then Det osynliga folket, they’re quite different formally. When you were making For Personal Reasons, was there something in the back of your head, other films or filmmakers?

MD: Jean-Luc Godard had a heavy influence on me. I think I saw almost all of his films up to that time. There was one film he made called Two or Three Things I Know about Her and it was his voice in second person. That’s how, I think I made For Personal Reasons. So, the whole time I was making For Personal Reasons, I was thinking of Jean-Luc Godard.

AZ: Then you made Det osynliga folket.

MD: Yes, that happened after I finished. But again, it also happened after I had met Frederick Wiseman. [Laughs.] When I was making that film, I was thinking of Frederick Wiseman. Because he looked at society. He looked at the problems without judging or solving them.

AZ: Did you see his films already in New York?

MD: I saw Titicut Follies in New York, because my wife had a girlfriend who had a brother, who was in one of those hospitals in New York.

AZ: There was a big discussion around that film?

MD: Huge discussion and debates around that film. So, when he came here to Stockholm, I said, “Well, I got to meet him”.

AZ: Det osynliga folket happened in 1973?

MD: Yes, sitting in the student café [in Lund]. The students could sit and talk and supposedly do their homework. [Laughs.] Some homework was done. But the foreign students all had a strong sense of identity, who we were. We had one Englishman named David Westman, who had a PhD in political science from Lund university. He had all the education we needed, about Sweden, Europe and sociology. He used to say things like, “You know, here we all sit and we’re all foreign students. But we’re really all invisible”. He said, “When you go beyond the student buildings into town, you’re invisible. You don’t exist”. Before coming to Sweden, I had read a book entitled The Invisible Man by the African American author Ralph Ellison. Based on the same theme, it was about how Black people in America work hard, buy houses, buy cars, but basically are invisible in the United States. That’s the way it was in the thirties and forties and fifties. Now it may be a little different. [Laughs.] But here in Sweden, we are the invisible people to the majority of the population, and that’s why that film has that name.

AZ: But did the film happen through SVT?

MD: Because I went to the same producer. This time they were very generous and didn’t ask me for a script or anything. They said, “Take a camera, take a tape recorder and go to Lund”. [Laughs.] So, that’s what I did. I had good people around me. One good friend of mine was named Urban Blomquist. He became my right-hand man because he knew Swedish. Everything got put together correctly because we all had the same idea: That we were the invisible people and that this was a great moment to say so. Like Nancy Ressaisi said in the film, “They never tell you that you can’t do this because you’re black; but you see everybody else getting in and you are not”. That’s the way it is in Sweden, right up till today.

AZ: And with Det osynliga folket was there more of a public debate?

MD: The reaction was fantastic because they had a big debate in Swedish TV, they invited me, but I didn’t want to sit in the audience. I didn’t understand what people were saying. I spoke almost no Swedish at all then. I stood behind the scaffolds while people talked. One of the conclusions they came to was that since the government had this policy that was almost 100 years old – that any immigrants coming to Sweden had to do all their business at the police station. That changed. Eventually they had something called ‘Invandrarverket’ and it lasted for about ten years, then they changed it to ‘Migrationsverket’.

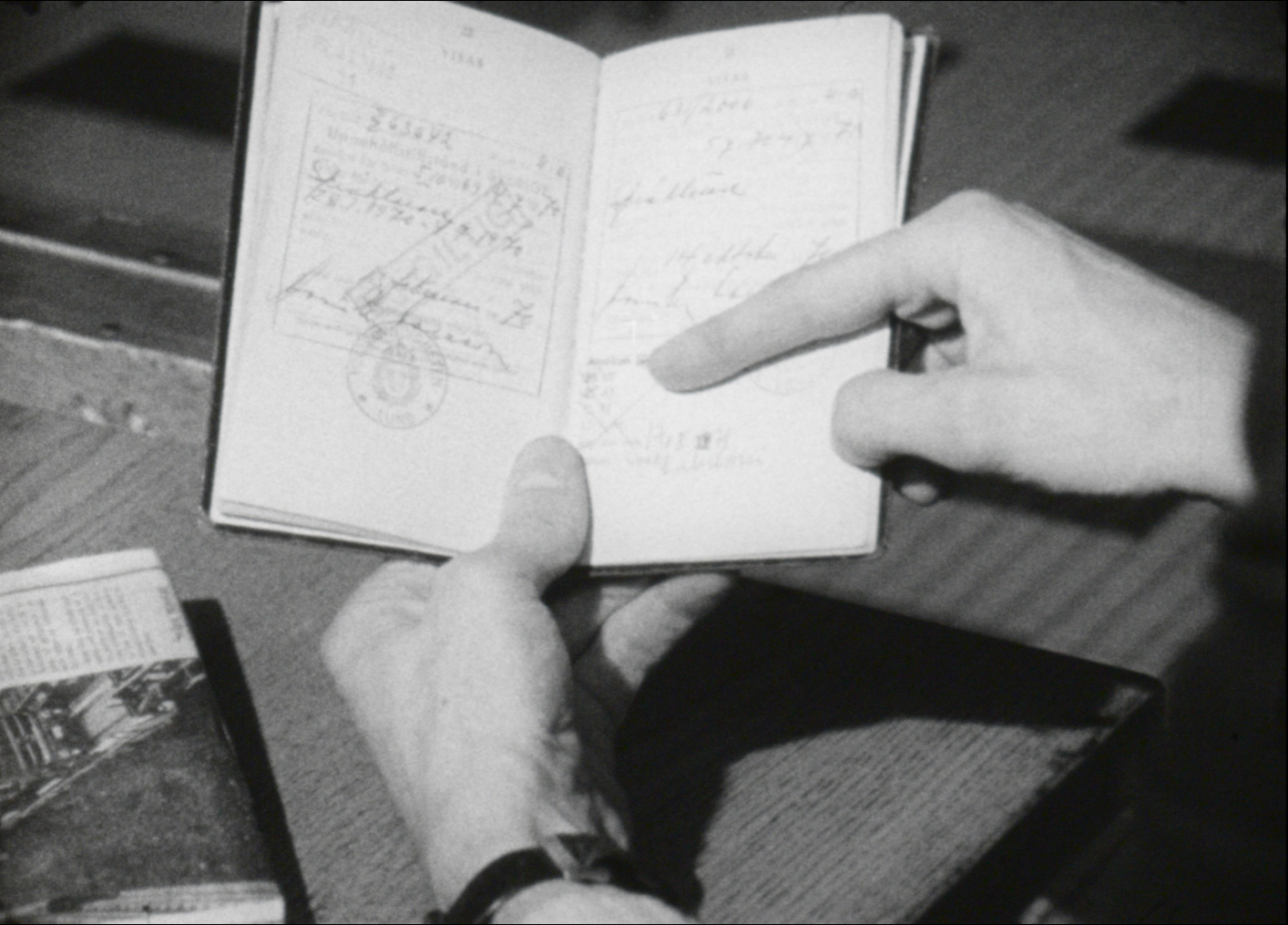

Det osynliga folket, Madubuko Diakité, 1971

AZ: Your filmmaking was much connected to public service but what was your relation to cinema at this time?

MD: I had no interest in cinema. I was interested in screening in small places, small theaters and schools. I was never interested in cinema.

AZ: Could you tell me a little bit about Dreams of G?

MD: Dreams of G was made before For Personal Reasons, and that is a real artistic film. It was probably finished in early 1970 before I came back to Sweden. Basically, it’s about a girl, who happened to be my wife at the time. She’s walking along, twirling this little silly purse when she hears bells and she starts looking and listening, trying to see where the bells are coming from. All of a sudden, she sees these people swinging on a rope under a tree. All they did was swing back and forth on the rope in front of a tree and then the magic came in. My late friend Boris’s editing. He knew how to jump-cut very well. “You always cut on movement”, he says. It’s a kind of mystic film, maybe even surrealistic.

AZ: Then after Det osynliga folket, it’s En dag på Mårtenstorget. But are there more films in between, because it’s quite a long time-span?

MD: Yes, that’s true. Between 1973, Det osynliga folket and En dag på Mårtenstorget in 1981. I was struggling here in Sweden and then I went to Nigeria in 74.

Dreams of G, Madubuko Diakité, 1970

AZ: You went to Zaria in northern Nigeria, right?

MD: In 1974, I wrote to my stepfather who was still alive in Nigeria. I said, “Well, I have a master’s degree from The Swedish Film Institute in Stockholm. Do you think anybody there wants to hire me?” I was being naive. All of a sudden, I get this letter from Ahmadu Bello university in Zaira. I said, “They want me to come and sent me a contract, so I guess I have to go”. I told people what kind of equipment they would need: an Eclaire Acl camera and a Nagra SN recorder. Oh yes, I bought a Bolex Rex 4 for them too. They sent me a check for $10,000 to send them the equipment.

AZ: Because you lived to Nigeria as a teenager?

MD: Yes, for five years. When I got the check, I needed to buy the equipment for them. I didn’t know where to buy it in Sweden. So, I went to New York, to a company that always sold us our film equipment when I was living and working there. I got everything. They packed it all in a big crate and shipped it to Zaria.

AZ: Was it a different country you came to than the one you left as a teenager?

MD: Totally! First of all, I was now in the north. The north was, and still is, very undeveloped.

AZ: You were in the south as a teen?

MD: Yes, I grew up in the south, 3 years in Lagos, then 2 in Enugu. But now I’m in the north. It was very weird to be there. But eventually I got to the university and they were happy to see me and they took me to my office.

AZ: You were basically a small studio at this point?

MD: Yes, I was, and there was no editing equipment at all. That will come later, they said. So, there was nothing to do there but run around. I had my own still cameras, a Russian-made imitation of the Hasselblad.

AZ: You also had a team?

MD: It was just me and the guy who was my assistant. No sound technician. But I had to interview people and when I had made my selection of two or three people to be on the team as writer, editor, lighting technician and sound technician. When I made my selections, they told me, “You can’t have them”. They were all skilled people from the southern part of Nigeria. The director of the institute was an Englishman, and he sat me down and explained it all to me. He said, “Nigeria is in the process of indigenization”. Because there was around a thousand expats working at the university to get it started, he said “In five years, none of these people will be working here and that includes you too”. He said, “But they want you to get it started. Teach some native guys how to do these things and then say goodbye”. So, I said, “Well, that’s it. I’ll just take pictures of what I can.” It was the most surrealistic situation: the streets were dangerous, there were no streetlights, there were poisonous snakes and scorpions were everywhere. I did get to meet other Americans there, at least three were African Americans. And besides my assistant, who had some photographic experience, there was no one else who had a clue about how to make films.

En Dag på Mårtenstorget i Lund, Madubuko Diakité, 1981

AZ: You realized the impossibility of this situation?

MD: Yes, I did. The Centre had a Museumologist. He and his wife were from Germany, and they had this huge house with a big walled compound and two guard dogs. They had four Tuaregs who were guarding the area. It was very surrealistic. The Museumologist was supposed to collect items and build museums. But because of local politics, I don’t think he ever did that anywhere in Zaria. He and his wife just sat there having parties and drinking beer and whiskey. So, on December 17th, I got on the plane for Lund. Then in January, [my son] Jason was born. We were all alone, it’s a horrible thing to be foreigners, being alone and having a baby. No aunts, no cousins and no sisters – terrible! Around the beginning of February, my wife and I decided I should try Nigeria again, so I went back. I thought I’d give it another chance and shoot something.

AZ: Do you remember what it was?

MD: Yes, because when I got back the Director told me that a new Emir of Zaria was being coronated. I wanted to film the coronation and my assistant who was from there, he said, “Well, we have to ask the permission of the emir before we film him or the coronation”. We had to go through certain procedures when it came to getting to see the Emir. So, when we got to his palace, we had to take our shoes off outside of the Emir’s house. We then had to walk a few steps in and when we were like 15 meters from where the emir is sitting, we had to get on our hands and knees. Nobody walks up to the Emir. It doesn’t work like that. So, we went there, and we had our heads down and my assistant told the emir, who we were and that we want to make a film of his coronation. He said, “Okey, that’s good”. Then the emir asked my assistant, “Who is this man?”, meaning me. And my assistant said, “He’s an American. A man from America”. Oh, said the Emir. “A Ba-American”. We all smiled, and my assistant and I backed out politely. After we left, I thought to myself, how glad I was that he didn’t think I was a “Ba-Igbo”, or someone else from a Nigerian tribe. I would have been dead! That’s the way life was in Northern Nigeria.

AZ: Before continuing with Zaria, we first spoke about you being exposed to European cinema. But now you’re living in your teenage home, was that ever an interest for you in African cinema?

MD: Absolutely. I met filmmakers in Grenoble. They were from Cameroon and they were from the French speaking Africa, Cameroon, Senegal, Ivory Coast and Burkina Faso. Those people I met.

AZ: Was that your first meeting with African filmmakers or African cinema?

MD: No. I saw films by Ousmane Sembene in New York and met him briefly once. But in Nigeria, when I was there, there was no talk about Nigerian filmmakers. But I did meet some cinema owners. They were Lebanese. I met one guy in particular.

AZ: In Zaria?

MD: Yes, because in Zaira they were showing Hong Kong karate movies in their theaters, and a few Spaghetti Westerns.

AZ: But they were not showing African filmmakers?

MD: No, not in 1974–75. No way. I said to Harry [the Lebanese cinema owner], “You don’t ever show any films from Senegal?” He said, “No, why should I? They speak French. These people speak English.” I said, “Well, what would you say if some Nigerian filmmaker, decided to make films and they wanted to show the film in your theater?”. He said, “I would boycott them, I wouldn’t let them be shown, because there’s no money in them”. Then I said, “If the Nigerian government wanted to take over all the theatres, what would you do?”. He said, “Very easy. We’d shut down the distribution, they don’t have a distribution of anything. We’ve got it all”. So, it’s a good thing that Nollywood emerged in Nigeria because they’re shooting on video. They’re shooting their own stuff, putting it on CDs or DVDs and selling them all over like hotcakes.

AZ: But it’s much a result of the whole big machine of cinema. It’s an architecture, an apparatus, a business model and this anecdote you were telling about the cinema owner, who said, there is no money in this. It’s interesting to think about those two poles, if you don’t get the means of production, then you create the means of production with the DVD.

MD: Yes, that’s what they did. They don’t give a damn about the theaters anymore. I wonder how many theatres are running in Nigeria now, probably none. So, on the day of the coronation of the Emir we had only a little bit of film to shoot. But we couldn’t develop it. They had to be sent to London to be developed. I never saw anything filmed there at that time. Years later, I met a Danish woman and there she’s sitting with some of my film ideas in a film that she got all the credit for.

AZ: This was the footage that you had shot?

MD: Some of it was the footage I shot, but not all of it. She brought a lot of her own film and developed the footage. But some of the statements she made I had heard from my assistant, who probably gave them to her too. It’s all surrealistic, so I can’t claim anything but the photos I took down there on my Russian Hasselblad imitation.

AZ: What happened after that?

MD: Well, after the visit to the Emir, we were able to stand on top of the car and shoot some photos of the Emir and the crowd. I ended up shooting a lot of people, thousands of people. I got photographs of that but the moving pictures I don’t have. But I went back, it was 1975 when I left [Nigeria]. I came home to my family and started a photography business because I had cameras, I brought with me from New York back in 1970.

AZ: You were working as a photographer when you came back?

MD: Yes, for a while. People would call me if they needed a photographer. It wasn’t much business because I didn’t speak much Swedish. Then I went from that to teaching.

En Dag på Mårtenstorget i Lund, Madubuko Diakité, 1981

AZ: Did you become tired of making films after Nigeria?

MD: No, I never did. But between 1975 to 1978, I didn’t make any films. In 1979 I worked at Swedish Television in Örebro briefly.

AZ: You worked as an editor there for TV?

MD: Yes, but that was a disaster, I must admit. Because of the language.

AZ: But you were editing programs basically?

MD: Just junk and a little bit of sports. They got me to Örebro and stuffed me into a student room. Nobody talked, nobody communicated. Working for Swedish Television, it’s a very close institution. It’s not a happy institution.

AZ: So, between these years, there’s many things happening, raising a family and trying out different jobs at the time?

MD: We got divorced, and that was hard. The only good thing that happened was that the professor at the film institute, Rune Waldencrantz, got me on the doctors list for PhD [in film history] at ‘Filmvetenskapen’. Waldencrantz, he was the first person who had faith in me. I was in ‘Filmvetenskapen’ from 1971 till 1983. That’s where I got my bachelor and my master’s degree in 1973. I came back to ‘Filmvetenskapen’ in 1978.

AZ: But then there is a film again in Lund?

MD: Then I came back. I found this Eclair which was being sold by someone from ‘Sveriges Radio’ in Gothenburg. Unfortunately, I had to sell all my [previous] cameras. I had to eat.

AZ: But then you made En dag på Mårtenstorget?

MD: Yes, that was fun, it was with students. They were Swedish students for a course in film studies. There was a time when ‘Folkuniversitetet’ decided they were going to upgrade the type of courses they were giving. I taught drama and film. But then the government smacked them down and gave all their courses to Lund University.

AZ: But it’s an exciting premise to have the ‘Filmvetenskapen’ so close to making films. You were bridging the gap, it most have been, at the time, a very unique thing?

MD: I think it was. I can’t think of any other of my colleagues who were making films. But they all knew that I made films because many of them had seen For Personal Reasons.

AZ: Did your colleagues have an interest in your films, showing them and talking about them?

MD: Some of them did. That’s how I ended up in the magazine Kaleidoscope.

AZ: Could you talk a little bit about how En dag på Mårtenstorget happened? Because it’s very intuitive in the way it’s shot. Was it shot by the students?

MD: Yes, most of it was shot by students.

AZ: But you also went to make a couple of more films with students?

MD: Yes, high school students with Vipeholmsskolan in Lund. They had a teacher and he needed a source for his students to go out and learn how to write English. I told him, “We can work together”, and he sent me students. Some wanted to write and some wanted make films. Those who wrote articles I published in a newsletter about Lund entitled The Lundian Magazine. So, we have quite a few short videos that the students made and we have lots and lots of magazines about Lund.

En Dag på Mårtenstorget i Lund, Madubuko Diakité, 1981

AZ: But then there’s a big break from filmmaking until you made a film about the situation for Afro-Swedes in Lund?

MD: Yes, that’s my latest film. It was just an interview with two colleagues. One had a PhD and one had a master’s degree. But they both identified as Afro-Swedes and they both had different opinions. One guy was clearly very happy to be an Afro-Swede. He had a Swedish mother and father from Tobago. The other guy was from Eritrea, he came here as an immigrant, as a refugee. He said, no, I don’t feel anything else but Eritrean. Which is the situation for Africans in Sweden and that might be my next project.

AZ: Your films has gained a bit of tension in the last couple of years, you were recently screened in Stockholm with CinemAfrica. Why do you think that your films have had such a resonance now?

MD: Thanks largely to Simon Klose who rescued them from my attic. He’s a filmmaker too, and one day he asked me where my films were and brought his big strong friend over, we went up to my attic and he carried the two boxes of films down. Now, people are glad to see that someone was working on those issues back in the 1970s. Those problems have been exposed. But am I going to get up and go out and demonstrate? No, I’m going to start making films again.

AZ: But regarding these issues is there something you get excited about, through your lens and your filmmaking?

MD: Yes, there is. Jean-Luc Godard gave us filmmakers a very profound statement many years ago that my friend Boris used to say all the time, that “truth is 24 frames per second”, and I still believe in that statement. I think that my next film will be a surrealistic film.

AZ: For Personal Reasons was recently acquired by Moderna Museet. How does that feel?

MD: That really feels good. I’m glad that they did that because I’m a Swedish filmmaker. I made For Personal Reasons and it has been distributed, sold to Swedish TV. I never promoted it as an American film, I never promoted myself as an American filmmaker. I just happened to have been born there.

AZ: But would you say you’re a Swedish filmmaker then?

MD: Yes, I would say that. I’m very proud to say that now.

- Filmögon är ett förlag och en tidskrift för rörliga bilder och film:

- Filmögon