What would it be like to come to Sweden as a refugee today? As a child to political refugees this was the question I wanted to explore.Since being the child of political refugees raised in Sweden I did inherit refugee status when growing up. With time it has evolved to the constant status of being an immigrant without having migrated myself, and the experience of being born here but still being considered foreign. This gap has made me think of migration in relation to identity from a very early age, and has given me a perspective that has deepened at different times during my upbringing.

My attempt to artistically investigate the question above resulted in a project titled Proportions of Waiting (2015) that consists of several parts, which are listed below. The film The Refugee of the Sorrowful Figure is the key work in Proportions of Waiting and this text revolves mainly around the becoming of the video In the Waiting Room of Desertion.

Proportions of Waiting consists of:

1. The Waiting Room, which was an intervention in the form of architectural drawings of the waiting room in the Migration Agency’s headquarter in Norrköping that was reproduced on the floor of the gallery with adhesive vinyl, which turned the art gallery into a governmental authority.

2. The Waiting Room of Desertion, which was an installation inside The Waiting Room that consisted of two rooms. The outer room had the measurement of the visiting room in the Detention Centre and the inner room had the measurement of the kitchen in the apartment where a refugee lived during his five years in Sweden. None of the rooms had ceilings. When the installation was exhibited outdoors at the Museum Anna Nordlander I used iron plates on the surface of the walls, which then rusted during the four-month exhibition period in the summer of 2015. When these three parts are presented together, the viewer moves from a public space, to a semi-public, and then to a private space. These three rooms are the three spaces the refugee had access to during his five years when waiting for the final decision from the Swedish Migration Agency on his asylum application.

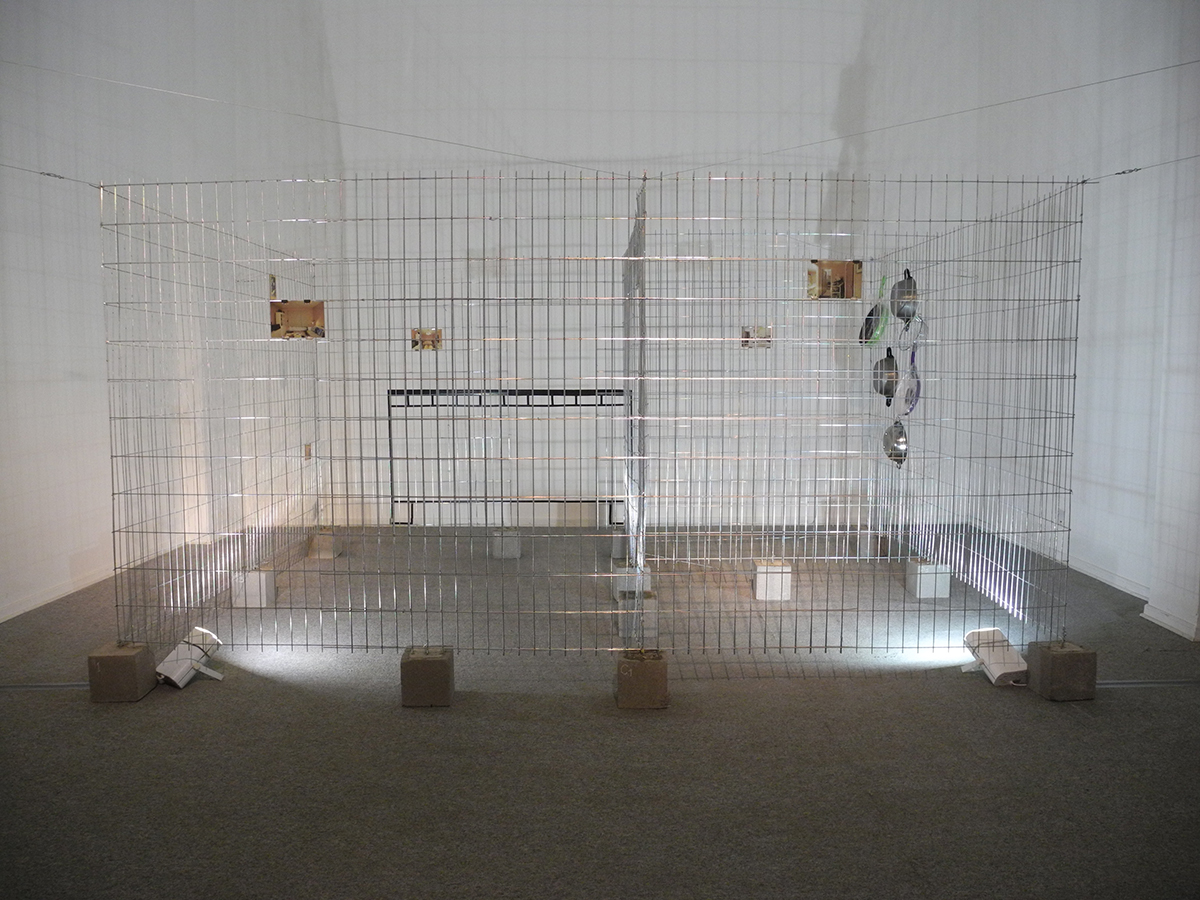

3. The Flat, which was an installation of the refugee’s empty flat , made of galvanised steel at a scale of 1:2, with transparent photographs at eye level that allowed viewers to see the interior of the flat from the outside.

4. The Detention Centre, which was an installation and scenography in the form of a room that was an exact copy of the visiting room at the Detention Centre. The main part of the film The Refugee of the Sorrowful Figure was shot in this room. When presented at Eskilstuna Konstmuseum, the film was screened in a room adjacent to The Detention Centre.

5. The Refugee of the Sorrowful Figure (43 min 52 sec), which is the central piece of Proportions of Waiting and will be described and discussed in the following text.

6. In the Waiting Room of Desertion, which is an 8 min 52 sec video in nine scenes in which I recite chosen extracts from Sarah Kane’s play Psychosis 4:48. Sometimes it was displayed on a monitor next to The Waiting Room of Desertion and sometimes I used the sound of the video inside the inner room of The Waiting Room of Desertion.

The Waiting Room, Haninge Konsthall spring 2018. Photo: Paula Urbano

The Waiting Room of Desertion, Art Lab Gnesta, oct-nov 2014. Photo: Paula Urbano

The Waiting Room of Desertion, Kristianstad Art Gallery, spring 2016. Photo: Paula Urbano

The Flat, MAC Quinta Normal, Santiago de Chile. Spring 2015. Photo: Paula Urbano

The Flat, MAC Quinta Normal, Santiago de Chile. Spring 2015. Photo: Paula Urbano

The Detention Center, Eskilstuna Konstmuseum spring 2015. Photo: Paula Urbano

In order to write about the video In the Waiting Room of Desertion I have to briefly explain why I felt inclined to make Proportions of Waiting and how In the Waiting Room of Desertion relates to the 45-minute film The Refugee of the Sorrowful Figure and The Waiting Room of Desertion.

I was born in Sweden, but my parents came to the country as political refugees in 1976. Shortly after their arrival my brother was born, and I arrived in 1980. I had heard about the reception of my parents in Sweden but also later in life in the form of recollections from Swedes who made friends with Chilean refugees in the 1970s. My impression is that their arrival to Sweden was perceived as a positive encounter from both sides. My parents described the reception as warm and welcoming, that they felt solidarity and that they received help from Sweden. My father also fell in love with a Scandinavian woman and left my mother, which is another story. My father and mother have described the feeling of freedom that they felt when they came to Sweden. I guess they refer to being free from the catholic shackles they had experienced, a sense of freedom which to them was a very positive one. It is not strange that this sense of freedom is predominant as they were fleeing from Pinochet’s dictatorship to the democratic society of Sweden.

During the 90s the rhetoric and the discussions about refugees and migrants shifted in Sweden, which became most visible in politics in 2010, when the Swedish Democrats were first voted into the Swedish parliament. To me that shift in 2010 was palpable; since I was born in Sweden I regard myself as Swedish, but suddenly there was a political party in parliament that does not share my view. A political party that based (and still bases) their politics on categorising Swedish citizens and their Swedishness according to racial categories. As a person of colour, I felt targeted, as if my body, skin and hair colour suddenly had become a battleground.

The contrast between my parents’ description of their reception and the situation of today drove me to seek out a person that had come to Sweden recently and find out how it would be to arrive in the country today. My objective was to follow that person from the point of their arrival to Sweden and when their first asylum application to the Swedish Migration Agency was made and capture the process until the person received either a “yes” or “no” answer:

A black and white film of yes or no yes or no yes or no yes or no yes or no yes or no

When you work with other people’s life stories you have to be humble about what you receive. The result, as shown in The Refugee of the Sorrowful Figure, turned out to be a story that starts after the person I followed, received a rejection letter from the Swedish Migration Agency, until one year after his first deportation. The method I used was to follow him, believe in him, spend as much time as possible with him and document the process with my camera. I became his friend, his witness and a companion, and consequently the film is about our encounter rather than just his journey.

From the very beginning I made it clear that I wanted to do an artwork with him and follow his asylum application process, and the intended result would be a film or video piece. I showed him an earlier film that I had made, titled Mentiramente (2012), because it was the only piece I had made until then about someone other than myself. He agreed on becoming involved in the project and we started filming the first day we met. Footage from that day is in the first part of the film. We spent hours together during which he talked and I listened. Our relation when filming became almost like a therapy session—I would listen and not give advice or try to solve any problem, but rather be an active and supportive listener.

My art practice revolves around studies of the state of mind of existential uncertainty. This is a condition that arises when fundamental existential components are subject to unforeseen ruptures, and are questioned or changed more or less drastically or violently: a condition in which life is turned upside down or reality as one once knew it is altered or disputed. In my case this condition is set in motion by the fact that my self-perception as both Swedish and Latin American settled in Sweden, is disputed through the simple question “Where are you from?” The question premises not only that I cannot possibly be from here (Sweden) but also that the place/nation/territory of my actual origin is singular. The relationship between my experience of being of foreign descent and my self-perception as Swedish or belonging in Sweden is also the force field that my artistic practice inhabits and problematises. Through my artistic practice I pursue people who are in these kinds of situations or whose existential uncertainty I can recognise or desire to understand more closely. Initially I explored my own inquiries and experiences, but the last decade my focus has shifted towards the fate of other people who share the experience of existential uncertainty.

The film The Refugee of the Sorrowful Figure is about the encounter between me and The Refugee. I take part in the film as the narrator, as his friend or squire as I choose to say in reference to Don Quixote’s Sancho Panza and I make a statement in front of the camera (which underlines I speak from an embodied position) in the first minutes of the film. By reading my statement in front of the camera I take a step from without: the narrator appears as author, stating my intention. Adding this meta perspective is inspired by how Cervantes refers to “the author”, which is himself throughout the book Don Quixote. This clip was added in the editing process with Alexandra Litén. In previous work I have edited myself, but this project was so much larger than anything I had done before and I had so much footage that I needed to work with a professional editor in order to keep to the deadline. It was the first time I worked with an editor and I am still very thankful for her input and to Konstnärsnämnden who gave me a large grant. I could not have done The Refugee of the Sorrowful Figure without the both.

Still from film "The fugitive of the Sorrowful Figure". Photo: Paula Urbano

While working with real people, the difference with a more traditional documentary is that I strive to use an intersubjective perspective that allows a variety of parallel perspectives to be present in the work. In addition there are the quotes from Don Quixote and Psychosis 4:48, the letters from the Migration Agency written to The Refugee, and last but not least his own words, where I give equal space to his ambitions and wishful thinking as well as his reality.

“I am here in this Förvaret No 1.

Not sad. I think I am full with struggle, with power to go on. And I think I can win.”

In this text I refer to the protagonist as “The Refugee” for mainly two reasons: first, I chose to protect his identity by not using his name because of the risk he took by participating in the project. Second, as a critique of the anonymising used in mass media, but also within the migration system. In the quotes from the reports of Migration Agency they use words like “applicant” or “referent” instead of “You” or someone’s name. By using “The Refugee” the inhuman in this approach is highlighted, while you come closer to the protagonist in the film. Since you come closer, you start to feel empathy, so the distancing of the anonymising becomes uncomfortable, and you start to think about the use of the word. I would argue that throughout the whole film the viewer is confronted with their own preconceptions of what a refugee is, their opinion on what is a legitimate reason to stay, right and wrong and moral issues regarding how the migration system operates. The problem by naming him “The Refugee” is that it universalises his case, and I believe that every case is as unique and as complex as any human being. When you see the film you clearly see how limitative the migration system is as it forces all the unique individuals and needs in the rigid compartments of the law. The film itself does the opposite of universalising because it goes deep into his case. But in this text I choose to use that name anyway because the first reason I mentioned.

When we started to work we spoke in Swedish, but I realised it slowed down the communication so we quickly changed to English, which we both are more fluent in. The dialogue in the film is therefore in English, while the narrative voice is in Swedish. As English is not our first language there was always a distance, a lack of words and ways to express ourselves fully. We were still getting to know each other so I had to consider the natural urge in him to present himself as successful, despite or due to the hopeless situation in which he found himself. This lack of communication was at first frustrating, but later on it led me to reconsider my interpretations of him and his life story. I began to wonder: “How can I translate what I perceive from him in our meetings?” I felt I had to convey not only what he said when speaking to me in words, but also what I thought he expressed through his body language and inbetween his words, in his silences, and what he left out of the stories he told me. I decided I needed to add a point of reference that is well known but not a stereotype. The choice fell on Cervantes’s Don Quixote, which is not often referenced in a Swedish context. I believe that the Migration Agencys officers did not listen to him as I did. I think they just went on what he said but not why he said what he said. They cannot have made an effort to understand him and that is the largest difference between me and the Migration Agencys officers.

While working with Proportions of Waiting I was living in the home of the artist Karl Schultz-Köln, (as part of my Artist in residency at Art Lab Gnesta), and browsing in his library I found a little book, which was Cervantes’s Don Quixote in Spanish for beginners. I had not read the classic Don Quixote but as a Spanish speaking person I had thought many times that I should read it. Especially when I hear people brought up in a Spanish speaking country reciting Don Quixote or Sancho Panza I can envy that they have this common reference because they learn it in school. It reminds me of what I lack. I can reciprocate this feeling of lack, I thought, and read DonQuixote in easy Spanish. I read it in Swedish, I read it in English and I saw a clear resemblance with the man I was following. The hopefulness, the positivity, the sense of humour, and, most importantly, his braveness that is close to madness. Don Quixote dubbed himself a knight and The Refugee claimed he would be a Swedish citizen any day soon: “It is only a matter of time. My case is only a matter of time”, he said repeatedly. There were clear parallels with Don Quixote, so I decided to incorporate quotes from the book in the voiceover. In the process of making the piece, we read the book together when spending time at the Detention Centre before or after filming, and in the film itself.

Malin Alm in her studio. Photo: Paula Urbano

Aristotle says in the book Poetics

“What we have said already makes it further clear that a poet’s object is not to tell what actually happened but what could and would happen either probably or inevitably. The difference between a historian and a poet is not that one writes in prose and the other in verse…/ The real difference is this, that one tells what happened and the other what might happen. For this reason poetry is something more scientific and serious than history, because poetry tends to give general truths while history gives particular facts.”

I found the same quote in end of the second part of Don Quixote and I chose to have as the last words of the narrators voice:

“That’s where the truth of the history comes in, said Sancho. They also could have kept quiet about them for the sake of fairness, said Don Quixote, because the actions that do not change or alter the truth of the history do not need to be written if they belittle the hero. By my faith, Aenas was not as pious as Virgil depicts him, or Ulysses as prudent as Homer describes him. That is true, replied Sansón, but it is one thing to write as a poet and another to write as a historian: the poet can recount or sing about things not as they were, but as they should have been, and the historian must write about them not as they should have been, but as they were, without adding or subtracting anything from the truth.”

By using that quote in the end of the film I confirm my statement at the beginning of the film explaining why I used references from the literary world, reminding the viewer that I work from the position of the poet/artist in contrast to the one of a historian or academic.

I had my doubts about using such diverse references as Cervantes’s Don Quixote, written in the seventeenth century, and a text by the contemporary playwright Kane, but it felt just right, so I followed that feeling. I would argue that it is part of my method to put together things that do not naturally belong together and make it fit. I tested it by showing it to a few well-chosen people, among them a documentary filmmaker. Without describing or saying anything to her, she asked: “The words you say while you are driving the car, are those your words or his?”

That was exactly what I intended with the scene: to question who is speaking and who is being spoken of. With that scene there is a shift of subject position in the film: I speak out his feelings and when the piece Proportions of Waiting is shown as a whole, the spectator shifts between the position of The Refugee and the position of an officer of the Migration Agency.

I wanted to make the viewer feel the existential uncertainty that the protagonist was going through. In all of my work I strive to have a shift of positions: what if you were me, if I were him or her? I strive to have different perspectives on the same story and I want the viewer to physically and/or mentally enter another person’s world and literally feel what it would be to walk in that person’s shoes. I want the viewer to feel confused; what you understood five minutes ago can be completely the opposite of what you see two minutes later. I want you to question yourself and to see yourself from another perspective by making you shift positions when you experience my work. In the film The Refugee of the Sorrowful Figure there are two turning points, resulting in three versions of the story; first you feel a lot of empathy and solidarity, which after a while turns into scepticism and you feel fooled, that he is lying, and you are doubting his story and his reason for wanting to flee. Towards the end, in the last five minutes of the film, there is yet another turning point, which changes all you saw earlier and where you understand him more deeply. During these turning points the viewer faces their own assumptions about what a refugee is or can be. They are confronted with their own preconceptions that they maybe were not aware of when regarding themselves an open-minded antiracist person, or something similar.

This way of working is what I call the intersubjective perspective and I use this perspective in order to narrate as close as possible to reality as one lives it. Reality is contradictory, complex and it has no beginning or happy end as it is presented in both fiction and documentary. Even a film with a sad end often resolves the problem. The basis in dramaturgy is to solve the problem upon the story rests. For many people the problem has no clear or easy solution. Those are the life stories I am interested in.

I asked myself: How could I convey or translate these dark and gloomy aspect of The Refugee to myself and to the audience? I did not want to put words in his mouth or provoke him with questions to make him speak out when he chose not to. I was not at all sure how, but I wanted to include the despair respectfully. The least I wanted to do was to provoke a breakdown in front of the camera. Following his process was emotionally and mentally extremely demanding for me: I considered whether I could speak up about his despair and frustration and sorrow since I could sense it so vividly myself. This led me to Sarah Kane’s play Psychosis 4:48 which I had read fifteen years earlier.

The British writer Sarah Kane (1971-1999) wrote five plays during her short, but professionally intense career. Her last play was Psychosis 4:48, which she wrote in 1999, shortly before she committed suicide by hanging herself with her shoelaces after having miraculously survived an overdose of antidepressant tablets. Kane is known for her focus on redemptive love, sexual desire, torture, pain and death. Her plays are characterised by a poetic intensity, direct language, and violent stage actions with references to ancient plays and to the then contemporary Balkan war.

Psychosis 4:48 is highly fragmented and has no plot. In the script there is no indication of location, there are no names, no descriptions of who says what. Some pages consist of numbers without description or instruction of how to interpret them or what the numbers refer to. The reason I wanted to work with it was because I felt the text was open in ways different to conventional theatre. I read it as a description of the darkest parts of a psychotic and depressed state of mind, which she had when she wrote it. It is raw and the despair is so visceral that it is hard to read it all the way through. It is like staring at the sun: you need to protect yourself or use a filter. Yet it is enlightening, just like there would be no life on earth without the sun. Sarah Kane did not only describe the despair, she dramatised it and that can only be done by someone who really knows first-hand what it is like to be in such a situation.

I decided to work with an actor, Malin Alm as an instructor when working with Sarah Kane’s play Psychosis 4:48. I told her about The Refugee and all he had told me and together we read the play Psychosis 4:48. We started selecting scenes that resembled The Refugee and deleting the parts that did not come close to what he implicitly expressed through his body language or explicitly in words. We went through the text numerous times and deleted more and more until we had a very slimmed down version of the play. Then I started rehearsing the text and Malin filmed me with my pocket camera. Over and over again we rehearsed while recording my performance and deleting more scenes. In the end all that was left were twelve or thirteen short scenes, which in the final cut of “In The Waiting Room Of Desertion” were reduced to nine. When it was time for production I wanted to be able to focus only on the text and therefore I hired Dan Lageryd as photographer.

Working while stuck in a traffic jam. Photo: Dan Lageryd

Working while stuck in a traffic jam. Photo: Dan Lageryd

The day of production Lageryd, Alm, and I went in my car to Art Lab Gnesta, where we were to film. We got stuck in a traffic jam, and while stuck there we started to get stressed and were joking that the time to record was eaten up by the traffic jam, so we started to work in the car. Alm had the script and I was rehearsing the text while driving the car. Lageryd started filming and in the end this scene turned out to be the only scene from the excerpts of Psychosis 4:48 that was used in the film The Refugee of the Sorrowful Figure. Upon our late arrival at Art Lab Gnesta we shot the video In the Waiting Room of Desertion in the basement, a suitable location as backdrop. Later that year it was part of the solo show I had, titled In the Waiting Room of Desertion, at Art Lab Gnesta (October-November 2014).

Documentation of the exhibition In the Waiting Room of Desertion at Art Lab Gnesta 18 okt-23 nov 2014. Photo: Paula Urbano

The video In the Waiting Room of Desertion consists of the nine clips in which I read excerpts from the script, facing the camera. In the different parts of Proportions of Waiting I have adapted the piece to the site of presentation. When the video In the Waiting Room of Desertion was shown at Art Lab Gnesta it blended in very well with the site. I recorded all sound in the area and edited together with Zachris Trolin at EMS studios. The sound of the video is like a sound piece in its own right. I wanted to have a sense of displacement between the inner world and the outer world to mediate the psychotic state of mind. At Art Lab Gnesta I had the video in a room beside the main hall where the installation The Waiting Room of Desertion was installed. The sound of the video was in both rooms, where in the installation you “read” the sound as thoughts. I used the sound in the same way at Kristianstad Art Gallery. An example of the displacement in the first scene, which is quoted below, is that the image shows me standing in front of the camera talking to the viewer, but you hear sound of restless steps walking, in a circle in what you perceive as a small room. The sound conveys the inner world, while the image shows ”reality”.

I am sad

I feel that the future is hopeless and that things cannot improve

I am bored and dissatisfied with everything

I am guilty, I am being punished

I used to be able to cry but now I am beyond tears

I have lost interest in other people

I can’t make decisions

I can’t eat

I can’t sleep

I can’t think

I cannot overcome my loneliness, my fear, my disgust

I cannot love

I cannot be alone

I cannot be with others

I do not want to die

I do not want to live

Some would call this self-indulgence (they are lucky not to know its truth)

Some will know the simple fact of violence

This is becoming my normality

In the original script Kane writes “the simple fact of pain”, but I changed it to violence. This is the only change I made in the text and I would like to explain why. Pain and violence are closely interrelated; they are like two sides of the same coin. When you are a victim of violence, it causes you pain. However, the kind of violence that is referred to here is not a physical violence. It is another kind of violence, the violence that the oppressed is doomed to live under. The oppressed feel the violence but others cannot see it. They cannot go to someone to say “Hey stop hurting me!”, because it is invisible, yet they can feel it all the time because it is systemic. I had recently read Frantz Fanon’s Black Skin, White Masks (1952), which was a mind-blowing experience. Fanon says, as I remember it, that violence is the only way the colonised can be decolonised. He claims that violence can free the colonised from the violence they were forced to, that with violence the colonised can free themselves from the sense of inferiority the colonial situation has internalised within them. Violence is not the objective, but it is the only means to change the structure, to decolonise the colonised person. Fanon speaks of the violence turned inwards and Sarah Kane writes pain so I changed pain to violence for this reason.

RSVP ASAP

While following The Refugee I experienced that his life was characterised by waiting. He was at the Detention centre when we started to film. Detention Centre is where people are detained while waiting to be deported. After marrying at the Detention Centre he was waiting for an answer, after refusing one, two, and three deportations he was waiting for the answer from the Swedish Migration Agency. So the plea to RSVP ASAP in capital letters fits well to him, and constitutes one scene in the video In the Waiting Room of Desertion.

Please…

Money…

Wife…

Those words were written just like that in Kane’s script: one word on each line and no further description of who says it to whom. However, I interpret it as if the words were said by him, especially after his marriage at the Detention Centre. These lines become one scene in the video In the Waiting Room of Desertion. In this clip I added city sounds that I recorded in Teheran, as if they were said by a beggar on the street, because I thought of my mother who was a graduate maths teacher when she arrived in Sweden. She describes with disgust the sense of being regarded as a beggar when receiving welfare the first period after arriving. All she wanted was to work and be able to support herself and her family, but before learning the language, before settling she had no choice but to receive economic help. Despite what my parents felt at their arrival to Sweden as welcoming country, my mother describes the approach from some social workers as humiliating. She was very happy to get the work as a cleaning lady so that she never had to receive welfare again. After six years in Sweden she started to work as a maths teacher, what she had done already before coming to Sweden.

Documentation of the film shooting at Art Lab Gnesta. Photo Erik Rören

In one part of Kane’s script, which I chose to have in the video In the Waiting Room of Desertion, it seems as if the protagonist takes responsibility for all the atrocities of the world, one atrocity after the other, through the following words:

I gassed the Jews, I killed the Kurds, I bombed the Arabs, I fucked small children while they begged for mercy, I fucked small children while they begged for mercy, the killing fields are mine, everyone left the party because of me, I’ll suck your fucking eyes out send them to your mother in a box and when I die I’m going to be reincarnated as your child only fifty times worse and mad as all fuck, I’m going to make your life a living fucking hell I REFUSE I REFUSE I REFUSE LOOK AWAY FROM ME.

I chose to include this part as it shifts perspectives and as a comment on how some people think it is legitimate to speak about migrants, foreigners, refugees or people of colour. I, with my non-white body, reading the lines and taking responsibility for all the worst atrocities committed by human kind, I wanted to bring out the absurdity of such ideas, making you realise that it is not possible for one person to do all those things while commenting on the fact that there are people who seriously have such thoughts about refugees, migrants or people of colour.

You do not need to be an academic or researcher to understand that this process is inhuman: following The Refugee from the moment he received his first rejection from the Swedish Migration Agency, his attempt to appeal, waiting, when receiving a new rejection, sending in a new appeal, waiting again, hoping, fearing what he would go back to, receiving the last rejection, waiting in the Detention Centre in Märsta, hunger striking at the Detention Centre, when reading the article about him in a local newspaper, resisting the first deportation, waiting in the Detention Centre, facing a second deportation, resisting again, being sent back to the Detention Centre, more waiting, being transported to another Detention Centre, waiting once more, marrying at the second Detention Centre, waiting again, hoping for his last chance, waiting until they just let him out of the Detention Centre without deportation, but without giving him any papers, when returning to the flat without solution, waiting yet again until he decides to give up and take the flight to Baghdad.

I have learnt enough about the migration system and of what it does to the mind and body of the person going through that. It is not only that you have to wait, it is that you do not know for how long. It is this waiting in uncertainty that is the most difficult part to handle; it causes a pressure that increases anxiety, because the person going through the process does not have control. This process can slowly break down any healthy human being. This system drives people crazy.

A person can be sent to a Detention Centre as a punishment, but prior to that there has been no trial, and there is no time limit either for how long their stay will be. It is a waiting in uncertainty. The Migration Agency evaluates the person’s life stories and there are certain rules the system follows. I wanted to expose the work of the Migration Agency, and therefore I use quotes from the letters sent to The Refugee in the film The Refugee of the Sorrowful Figure. The bureaucratic language sounds even more dehumanising when describing a person’s life story, their upbringing, and especially the love relations sound almost absurd. All this I wanted to demonstrate in the piece. I don’t think I have any answers, but with this work hopefully a larger amount of people gain insight in these processes and become involved as fellow humans, as citizens, as volunteers or in any other way they can engage in this cause.

The process of making Proportions of Waiting started in October 2013, and I thought it would end with the first exhibition at Katrineholms Konsthall in January 2015, but it was followed by an uninterrupted tour that lasted until May 2016 at Kristianstad Konsthall. However, I continued to receive invitations to solo or group shows. The last invitation to show this piece came from Haninge Konsthall where I had a soloshow in 2018. And this text is written five years after I finished the piece. I am still in contact with the man who is no longer a refugee. I would like to make an epilogue on what happened after The Refugee of the Sorrowful Figure ends. Inshallah I will do that.

Finally I would like to end with the quotes from the last scene of the video In the Waiting Room of Desertion that summarise an essential part of the problem; the human need to be seen and heard.

Validate me

Witness me

See me perceive me

Love me

my final submission

my final defeat

watch me vanish

watch me

vanish

watch me

watch me

Referenser:

The party gained 5.7% of the vote in 2010, which has since then risen to 17,53% in 2018.

Kane, Sarah. Complete Plays by Sarah Kane. London: Bloomsbury. 2001.

Mentiramente is an experimental short film about one of the approximately 400 children born in a clandestine detention and extermination centres in Buenos Aires during the dictatorship in Argentina.

The statement reads as follows: “As an artist I investigate existential uncertainty and that is why I went to the Detention Centre to meet someone who lives under oppression. This is the film about our encounter.”

Statement by The Refugee in The Refugee of the Sorrowful Figure.

Quotes from Don Quixote and from letters from the Migration Board and different interviews made in embassies and offices.

Kane, Complete Plays by Sarah Kane, p.

Ibid., p. 214.

Ibid., p. 226.

Ibid., p. 227.

Ibid., pp. 243-244.